Alabama has scheduled a lethal injection for a man convicted in the 1997 deaths of four people, including two young girls.

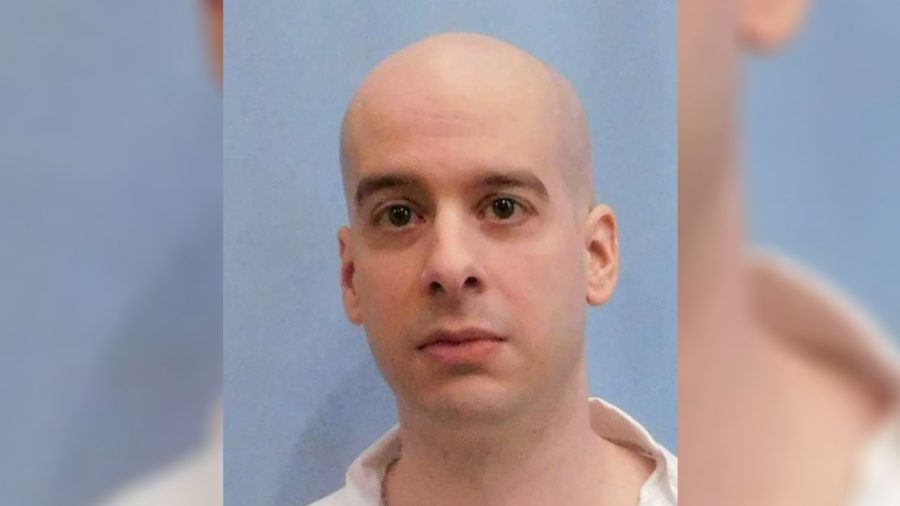

The Alabama Supreme Court set a May 16 execution date for Michael Brandon Samra, 41.

Michael Brandon Samra is scheduled to be executed in Alabama in 22 days, 1 hour and 47 minutes. https://t.co/ctf8v5pA3N

— The Next To Die (@thenexttodie) April 24, 2019

As a teenager, Samra was convicted of helping his friend Mark Duke kill his father Randy Duke, his father’s girlfriend Debra Hunt and her 6 and 7-year-old daughters.

Prosecutors said the Shelby County slayings happened after Duke became angry when his father wouldn’t let him use his truck. They said the teens executed a plan to kill Duke’s father and then killed the others to cover up his death.

Authorities say Mark Duke killed his father, Hunt and one of the girls, and that Samra slit the throat of the other child at Duke’s direction while the girl pleaded for her life.

“The murders which were committed with a gun and kitchen knife were as brutal as they come,” lawyers for the state wrote in the motion to set an execution date.

Duke was 16 at the time of the slayings. Samra was 19. Both were sentenced to the death penalty. However, Duke’s death sentence was converted to life without parole after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled prisoners couldn’t be put to death for crimes that happened while they were younger than 18.

Samra’s attorney wrote in a court filing that Duke was the driving force behind the slayings and prosecutors have acknowledged Duke was the “mastermind” while Samra was the “minion.”

Defense lawyer Steven Spears also wrote the case also involves the peculating legal issue of whether people should be executed for crimes committed when they were younger than 21.

In a separate death penalty case, a judge has scheduled a June trial on another inmate’s challenge to Alabama’s lethal injection process. A federal judge earlier this month stayed the execution of Christopher Lee Price. A divided U.S. Supreme Court vacated the stay, but the decision came after the death warrant expired.

Price has requested to be put to death by breathing pure nitrogen gas. Alabama authorized nitrogen hypoxia in 2018 as an alternative for carrying out death sentences, but has yet to use the method.

Scheduled Execution Arrives for Racist in Texas

The scheduled execution of an avowed racist who orchestrated one of the most gruesome hate crimes in U.S. history was executed on April 24, in Texas for the dragging death of a black man.

John William King received lethal injection for the slaying nearly 21 years ago of James Byrd Jr., who was chained to the back of a truck and dragged for nearly 3 miles along a secluded road in the piney woods outside Jasper, Texas. The 49-year-old Byrd was alive for at least 2 miles before his body was ripped to pieces in the early morning hours of June 7, 1998.

Prosecutors said Byrd was targeted because he was black. King was openly racist and had offensive tattoos on his body, including one of a black man with a noose around his neck hanging from a tree, according to authorities.

King, 44, was put to death at the state penitentiary in Huntsville, Texas. He was the fourth inmate executed this year in the U.S. and the third in Texas, the nation’s busiest capital punishment state.

Witnesses are being led across the street, a sign that the John William King execution is expected soon. #SETXNews @BmtEnterprise pic.twitter.com/CJkTWvfCol

— Ronnie Crocker (@rcrocker) April 24, 2019

King kept his eyes closed as witnesses arrived in the death chamber and never turned his head toward relatives of his victim. Asked by Warden Bill Lewis if he had a final statement, King replied: “No.”

Within seconds, the lethal dose of the sedative pentobarbital began taking effect. He took a few barely audible breaths and had no other movement. He was pronounced dead at 7:08 p.m. CDT, 12 minutes after the drug began.

As witnesses emerged from the prison, about two dozen people standing down the street began to cheer.

King’s appellate lawyers had tried to stop his execution, arguing King’s constitutional rights were violated because his trial attorneys didn’t present his claims of innocence and conceded his guilt.

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected King’s last-minute appeal.

“From the time of indictment through his trial, Mr. King maintained his absolute innocence, claiming that he had left his co-defendants and Mr. Byrd sometime prior to his death and was not present at the scene of his murder. Mr. King repeatedly expressed to defense counsel that he wanted to present his innocence claim at trial,” A. Richard Ellis, one of King’s attorneys, wrote in his petition to the Supreme Court.

The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles also turned down King’s request for either a commutation of his sentence or a 120-day reprieve.

Over the years, King had also suggested the brutal slaying was not a hate crime, but a drug deal gone bad involving his co-defendants.

King, who grew up in Jasper and was known as “Bill,” was the second man executed for Byrd’s killing. Lawrence Russell Brewer was executed in 2011. The third participant, Shawn Allen Berry, was sentenced to life in prison.

Less than 30 minutes away from the execution of John William King. King is said to be the ringleader in the dragging death of James Byrd Jr. Lawrence Russell Brewer was executed in 2011 and Shawn Berry is currently serving life in prison. pic.twitter.com/ZqejoNPJXF

— Makensie Hinkle (@MakensieTVNews) April 24, 2019

King declined an interview request from The Associated Press in the weeks leading up to his execution.

In a 2001 interview with the AP, King said he was an “avowed racist” but wasn’t “a hate-monger murderer.”

Louvon Byrd Harris, one of Byrd’s sisters, said King’s execution sent a “message to the world that when you do something horrible like that, that you have to pay the high penalty.”

Compared to “all the suffering” her brother suffered before his death, Harris said King and Brewer got “an easy way out.”

Billy Rowles, who led the investigation into Byrd’s death when he was sheriff in Jasper County, said after King was taken to death row in 1999, he offered to detail the crime as soon as his co-defendants were convicted. When Rowles returned, all King would say was, “I wasn’t there.”

“He played us like a fiddle, getting us to go over there and thinking we’re going to get the rest of the story,” said Rowles, who now is sheriff of Newton County.

A week before Brewer was executed in 2011, Rowles said he visited Brewer, who confirmed “the whole thing was Bill King’s idea.”

Mylinda Byrd Washington, another of Byrd’s sisters, said she and her family will work through the Byrd Foundation for Racial Healing to ensure her brother’s death continues to combat hate everywhere.

“I hope people remember him not as a hate crime statistic. This was a real person. A family man, a father, a brother and a son,” she said.

By Juan A. Lozano and Michael Graczyk