Drug cartels and street gangs in Mexico are creating their own religions and altering beliefs in existing Catholic saints, in a move to create a new “narcoculture” that tries to morally justify crime and violence.

Some of these new figures of worship are existing Catholic saints, most of which have had their meaning altered for the narcoculture. Some are pulled from Aztec gods worshipped through human sacrifice, while others are new creations altogether.

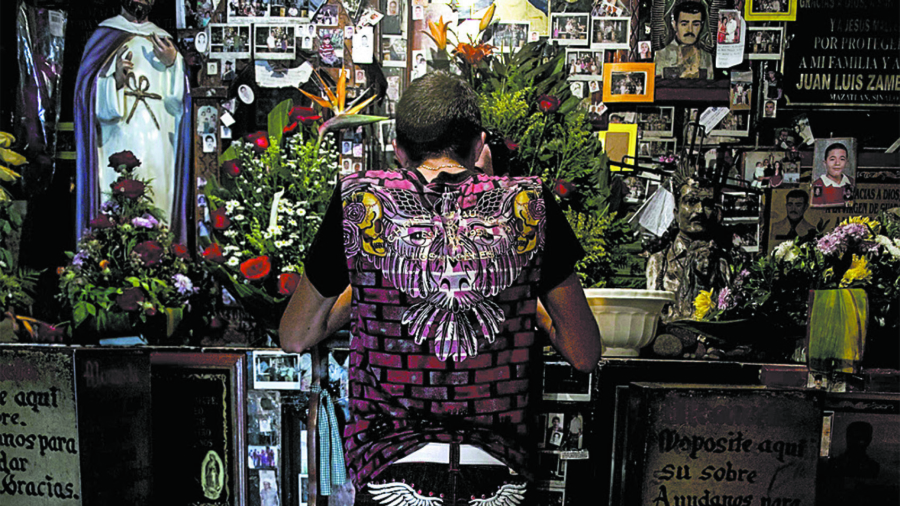

The two most popular figures of worship in Mexico are products of this new narcoculture. The most popular is St. Jude Thaddeus, also called “Saint Judas,” while the second most popular is a newly created folk saint called Santa Muerte, “Saint Death.”

What is taking place in Mexico is a form of “spiritual appropriation,” whereby the existing religion is being altered to justify a criminal insurgency, according to Robert J. Bunker, adjunct research professor at the Strategic Studies Institute at U.S. Army War College.

There is a spectrum of beliefs in Mexico that ties directly to the growth of crime. Bunker said at one extreme, there are those who adhere to traditional Catholicism and other morally based religions. At the other extreme “would be those individuals whom we consider to be ‘evil’ in their value system.”

Yet as the narcoculture continues to develop, it is becoming harder for people to differentiate the legitimate figures from the newly created “narco saints.” Bunker noted the case of Saint Judas, a legitimate Catholic saint now commonly worshipped for protection by smugglers, bandits, gangs, and drug cartel members.

He said a slightly more extreme case is the new “bandit saint,” Santo Niño Huachicolero, which is an alteration of a legitimate Catholic saint, Santo Niño de Atocha, or “Holy Child of Atocha.”

The Catholic News Service warned of the newly altered saint on May 12, noting that it was created by a gang of gasoline thieves known as “huachicoleros” southeast of Mexico City who altered the image of the Christ child to show him holding a gas can and hose. It cites Father Paulo Carvajal, archdiocesan spokesman, as stating: “This image can never be accepted. Being a ‘huachicolero’ is practically a crime. The church cannot be in favor of this, much less be in favor that images are used in this way.”

Carvajal said the new saint is being used to “deceive” people. Locals following the new saint have even protested to defend the gas thieves from law enforcement.

Bunker noted the significance of the phenomena, saying, “A venerated 13th-century Catholic saint has just been ‘spiritually hijacked’ by criminal elements in Mexico and recast as the patron deity of gasoline thieves before our eyes.”

With the creation of the new saint, “another demographic, albeit a relatively small one, has just further rationalized their criminal behaviors—which are at odds with state authority—by having someone to pray to in order to achieve success in their gasoline-stealing endeavors,” he said.

“From a Catholic Church and traditional Mexican societal perspective, another grouping of people just ‘jumped ship’ and went over to the narco and criminal elements of society in both their hearts and minds.”

‘Left-Hand’ Saints

The cases of sanctioned Catholic saints relate to spiritual appropriation, according to Bunker, whereby people are altering religions to justify acts—such as theft and smuggling—that would traditionally violate the religion.

On a spectrum that classifies beliefs on a “left-hand path” as ones that could be viewed as purely evil and on a “right-hand path” as ones of traditional morals, these new saints and figures fall from the middle to the left.

Bunker describes the spectrum of narco saints in the book “Blood Sacrifices: Violent Non-State Actors and Dark Magico-Religious Activities,” published in 2016.

Many cartels and criminal organizations in Mexico can no longer be viewed as merely conventional criminal groups, since many of them use narco saints to try to justify, or even sanctify, their crimes.

The Familia Michoacana cartel and the Caballeros Templarios cartel, which are two of the largest drug cartels in Mexico, worship the newly created San Nazario, “The Craziest One.” Their crimes play a direct role in their worship of their manufactured saint, who they believe requires torture, ritual killing, and cannibalism.

The Sinaloa cartel worships an unsanctioned saint of drug traffickers, bandits, and outlaws that they refer to as “Jesús Malverde,” also known as “Generous Bandit.”

Even “Saint Death,” which carries the image of the grim reaper, has a strong criminal following. According to “Blood Sacrifices,” the new “folk saint” is worshipped by the Los Zetas cartel, the El Gulfo cartel factions, and by many other gangs. Their worship often includes ritual killing, offering of human body parts, and cannibalism.

Mid-sized Mexican gangs and criminal outfits also have their manufactured saints. The Mexican Mafia, the Sureños, and Barrio Azteca, for example, worship the Aztec war god Huitzilopochtli. Bunker notes that while the deity’s requirements are often less gruesome than the new saints worshipped by many cartels, it is still used to justify the ideology of violent crime.

A Social Dilemma

For the rest of Mexico, the growth in popularity of narco saints presents a moral crisis, since they are not only being used to alter the traditional, morally based faiths, but also to create a new system of morals that supports violent crime.

In the conventional view of crime in the United States, people in criminal gangs are often motivated by financial gain, are pulled into lives of crime due to poverty or poor education, or join the gangs for a sense of belonging.

Bunker noted that while this conventional understanding of gangs and organized crime may still be largely accurate in the United States, it cannot be used to understand Mexican cartels or related Latin American gangs such as MS-13 and 18th Street.

These groups, he said, “are evolving into something much more dangerous that blurs our understanding of criminal activity and warfare.” He said they have become “challengers to the state” and have carved out their own territories in many countries where they can act with impunity.

The creation of new religions only adds to the severity of the threat. He said the groups’ criminality is “no longer just secular,” since they have added a new spiritual component to their actions, and they are now spreading these new ideologies among the general population—creating warped, “criminalized” societies.

Bunker noted that Americans and Europeans often see the world through “utilitarian, rationalistic, liberal democratic and secular colored lenses,” and these “perceptual biases” often prevent them from seeing that some groups may have perceptions completely different from their own.

“This is why—as a nation—the U.S. falls into recurrent traps of our own making,” he said, noting the U.S. attempts at nation-building in countries like Afghanistan that have often overlooked the tribal and factional cultures in those countries and their illicit markets in opium production.

The same has applied to other areas, including with drug cartels and terrorist groups. He said this perceptual bias has prevented many in the United States from being able to understand that “some people, such as members of a specific cartel or a terrorist group, may kill for sport and pleasure—as in the case of Los Zetas—or truly believe that they are doing god’s work while beheading someone, as in the case of Islamic State adherents.”

From The Epoch Times