This article was updated on Oct. 16, 2018

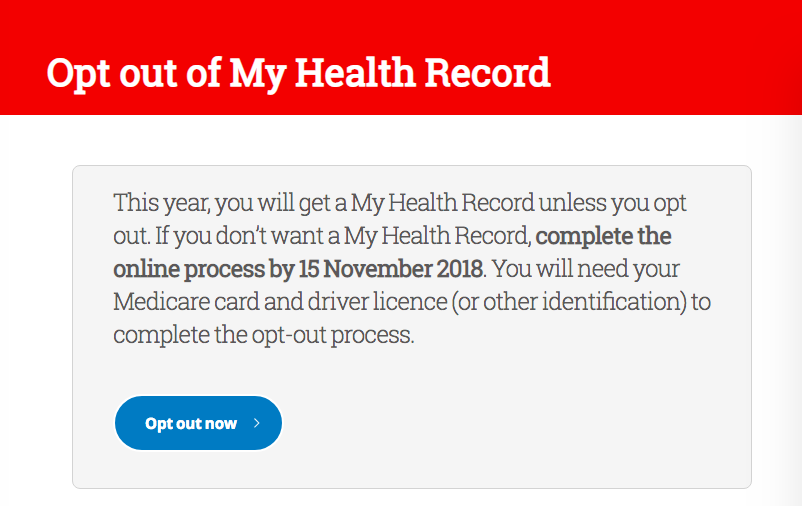

From July 16, Australians who do not want their medical records stored on the national electronic database, My Health Record, will have until Nov. 15 to opt-out.

The online database, launched in July 2012, comprises a person’s medical records—including their medications, diagnoses and treatments, allergies, and test results—that can be accessed by them and their healthcare providers. With an account, the person can control what is included in their record and who sees it.

The Australian Government announced in November 2017 that the database would transition from an opt-in to an opt-out model, which means that every Australian will automatically have a My Health Record online account by the end of 2018 unless they actively withdraw their consent.

My Health Record can allow healthcare providers to have faster access to a person’s medical history to help make better or faster treatment decisions. However, many have expressed concerns over the database’s security and privacy.

Benefits

President of the Australian Medical Association, Dr. Tony Bartone, said the service can improve patient care.

“It will assist in reducing unnecessary or duplicate tests, provide a full PBS medication history (thus helping avoid medication errors) and be of significant aid to doctors working in emergency situations,” he said, The Guardian reported.

“My Health Record will support practitioners, particularly those who may be seeing a patient for the first time, to have access to the information they need to best care for the patient,” he added.

Each year, an estimated 230,000 Australians are hospitalised due to medication errors. Deputy chair of the My Health Record expansion program, Dr. Steve Hambleton, told the ABC he believes the database can play a role in reducing that number. Hambleton said people most at risk of medication errors are those with complicated health problems who don’t have their medical history readily available.

“I have patients who run around with some raggedy pieces of paper in their pocket with their current medications on it,” he told the ABC.

Cybersecurity Concerns

Hambleton could not guarantee the database is absolutely secure. “I guess I can’t guarantee that there’s not a hole somewhere,” he told the Sydney Morning Herald (SMH).

“There may be a potential breach but that [will] not be the entire database,” he added. “[If there was], it’d be individual records and not all of them; and that’ll be tracked and it will show up.”

But Ralph Holz, an expert in cybersecurity from the University of Sydney, told The Guardian that a breach would affect the system as a whole, not just individual patients, and hackers could use the data to hold the department to ransom and or release the information to third parties.

“We always see a problem when we keep data in one place, especially if it is data that is a complete profile. There is a saying in computer science: once the data is out, it’s out. You can never get it back. The danger in building such systems is that it’s enough if they fail once,” he said.

On July 20, a major cyberattack on Singapore’s government health database stole the personal information of about 1.5 million—including Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong—in a “deliberate, targeted and well-planned cyberattack,” Singaporean authorities said. About 1.5 million patients who visited clinics linked to the Singaporean government health database between May 2015 and July 4 this year have had their non-medical personal particulars illegally accessed and copied.

Australian charity organisation Digital Rights Watch is urging everyone to opt out of My Health Record.

“No guarantees have being given that individual citizen’s personal information will be kept safe and secure,” Digital Rights Watch chair Tim Singleton Norton said, news.com.au reported.

“Health information is incredibly attractive to scammers and criminal groups … There are also concerns of the current or future access being granted to private companies,” the statement read.

In early July, news arose about Healthengine, an online doctor-booking service and one of My Health Record’s partner apps, had released patient information to third parties, including legal firms, the ABC reported. Healthengine has since announced it would stop sharing patient data, and Health Minister Greg Hunt has ordered an “urgent review” of the app.

But the database has been running for six years, and the government says there have been no breaches so far. According to the website, 6.19 million people are signed up, and more than 6,600 GPs, 3,700 pharmacists, and about 1,100 hospital organisations are connected to the service as of Oct. 7. The database has the backing of all of Australia’s peak health bodies, among them the Australian Medical Association, the Royal College of Australian GPs, and the Pharmacy Guild of Australia, the Guardian reported.

Privacy Concerns

Hambleton expressed concern about privacy with regard to the My Health Records Act. For example, currently, doctors can reject requests from authorities to obtain their patients’ medical records, by having them seek a warrant. But information uploaded to My Health Record can be accessed if there’s reasonable belief it can help prevent crime and improper conduct, or to protect public revenue, among other reasons.

“I don’t think a lot of doctors understand that medical records they upload to My Health Record in good faith—because they want to improve patient care—could potentially be used against people for administrative reasons in a way that they would never ever be happy that their paper records would be used,” Hambleton told SMH.

Bernard Robertson-Dunn, from the Australian Privacy Foundation, told the Guardian that the service may unwittingly share a person’s sensitive information with irrelevant people, calling it an “uncontrolled, uncurated, data dump.”

“Better sharing of health data among health professional is a good thing—as long as it is done in a controlled manner,” he told The Guardian. “But if somebody has mental health issues, you don’t want that shared with a dentist or someone who looks at your feet.

“An ex-partner or someone stalking a patient could get at that health information. If you’re at risk from someone, that person might access data about you that identifies where you live or what doctor you’re using.”

“If somebody has a medical condition that might result in discrimination—specifically HIV or mental health problems—they don’t want their data shared,” he added.

While those with accounts can control access to the record, including switching off their entire record and restricting access to it by setting a pin code, Dr. Trent Yarwood, an infectious diseases physician who represents digital advocacy group Futurewise told the ABC that many people may never know how to set their controls.

“Having [access controls] opt-in is complex, because it means it skews to people with better health literacy,” he told the ABC.

To Opt-In or Opt-Out?

In May, Tim Kelsey, head of the Australian Digital Health Agency, the organisation behind the records, said:

“There’s literally nothing in [a person’s My Health Record] until it’s activated at which point two years’ worth of your [Medicare Benefits Schedule] and [Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme] data—if you consent—will be uploaded,” he said, SMH reported.

After Nov. 15, there will be a month of reviewing who has opted out, and new records will be created mid-November. Those who don’t opt out in time can still cancel their records, but the information in it will still exist until 30 years after their death.

In a SMH opinion piece, freelance tech/culture writer Ben Grubb explains why he’s opting out.

“One of the main reasons I have decided to opt out is my lack of confidence in the government to secure its citizens’ data, and several breaches where information hasn’t been sufficiently secured.

Grubb details various ways in which a person’s data can be breached. But he adds that the benefits can outweigh security risks for some.

“If you suffer from chronic illnesses, have allergic reactions or anaphylactic shocks, and otherwise need information to be conveyed to a medical professional when you are unable to, then the benefits will outweigh the risks in a situation of life or death.”

Those who would like to opt-out can do so through My Health Record website, helpline 1800 723 471 or print forms at post offices. They will need to provide Medicare details and personal ID.

Reuters contributed to this report