Commentary

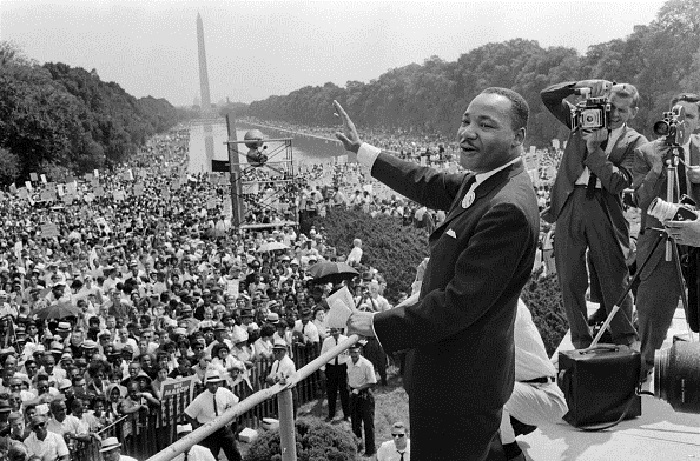

Each year, America celebrates the legacy and accomplishments of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And as we watch video clips of the “I Have a Dream” speech and see powerful photos of this civil-rights icon displayed across televisions and editorial pages, we tend to take a facile look at King’s work.

His deeper convictions are often overlooked as we mire ourselves in feel-good messages about nonviolent resistance and the abolition of racism and segregation.

King offered much more. In no place is this clearer than a rarely discussed book he wrote, called “Strength to Love,” in which he boldly and unapologetically called for mankind’s inner spirit to evolve into a better version of itself.

“Rarely do we find men who willingly engage in hard, solid thinking. There is an almost universal quest for easy answers and half-baked solutions,” he wrote. “Nothing pains some people more than having to think.”

Quotes like this are seldom mentioned in tributes to Dr. King. He challenged the nation’s social mores, not only on race issues, but on issues that still try us today.

“Success, recognition, and conformity are the bywords of the modern world where everyone seems to crave the anesthetizing security of being identified with the majority,” he wrote in critique of groupthink. He challenged us to not seek comfort with the herd. He implored us to look within to define our morals and to stand for what’s right, even when it’s not easy.

“Some philosophical sociologists suggest that morality is merely group consensus and that the folkways are the right ways,” he wrote, before warning us of the pitfalls of “rugged collectivism.”

Not even the church was spared from his censure, as he urged Christians to stand up as leaders—to stop taking polls and issue principled edicts.

“[M]ost people, and Christians in particular, are thermometers that record or register the temperature of majority opinion, not thermostats that transform and regulate the temperature of society,” he wrote. “We preachers have also been tempted by the enticing cult of conformity. … We preach comforting sermons and avoid saying anything from our pulpit which might disturb the respectable views of the comfortable members of our congregations.”

The Baptist minister had a raging fire in his belly that compelled him to speak truth, in all its forms. King, a man whose stature was 5 feet, 7 inches, had words and a way of delivering them that made him seem like a giant.

Like David fearlessly approaching Goliath, he even turned his attention to the American foreign-policy establishment.

“Millions of citizens are deeply disturbed that the military-industrial complex too often shapes national policy, but they do not want to be considered unpatriotic,” wrote Dr. King. “Some men still feel that war is the answer to the problems of the world.”

King was a champion of peace, not only for blacks in America, but for the entire globe. To him, the principle of nonviolence wasn’t simply an imperative for individuals, but for governments, as well.

“There may have been a time when war served as a negative good by preventing the spread and growth of an evil force, but the destructive power of modern weapons eliminates even the possibility that war may serve as a negative good,” he wrote.

Most remarkable about King is that, despite his ability to recognize evil in the world, he did not allow it to consume him. He saw the spark of divinity in all of God’s children and urged a life of compassion.

“[T]he evil deed of the enemy-neighbor, the thing that hurts, never quite expresses all that he is. An element of goodness may be found even in our worst enemy,” he wrote. “This simply means that there is some good in the worst of us and some evil in the best of us. When we discover this, we are less prone to hate our enemies.”

Many people have never been exposed to this version of King. One might suspect that the less-talked-about views of King are rarely discussed because they are destabilizing. They represent threats to established institutions that often divide, rather than unite. Though love and reconciliation were always the end goal for King, he sometimes delivered tough messages to push us there.

King wasn’t just a civil-rights leader who delivered a Kumbaya message of racial harmony. He beseeched substantial shifts, not only in individuals but also within churches, institutions, and the government.

As we pause in memoriam of King, let’s not simply remember the sermons and messages he delivered that make us feel comfortable—let’s remember all of them.

Adrian Norman is a writer and political commentator.

From The Epoch Times